There’s always a lot riding on how you choose to set up your business, especially in an industry as complex as transportation. Have you acquired a federal transportation license as a motor carrier (MC)? Are you operating as a freight broker or forwarder? Do you use owner-operators, and if so, are you in compliance with the Truth in Leasing requirements under federal transportation law (49 CFR Part 376) for the lease agreements you utilize?

On the surface, these may seem like straightforward questions, but the implications can be incredibly complicated. When considering your answers, you must think of contractual agreements; local, state and federal regulations; insurance coverages; and driver checks and qualifications. And that becomes more complex still when you factor in the looming specter of independent contractor (IC) misclassification.

Thankfully, finding a path through these concerns starts with one basic question.

What’s your model?

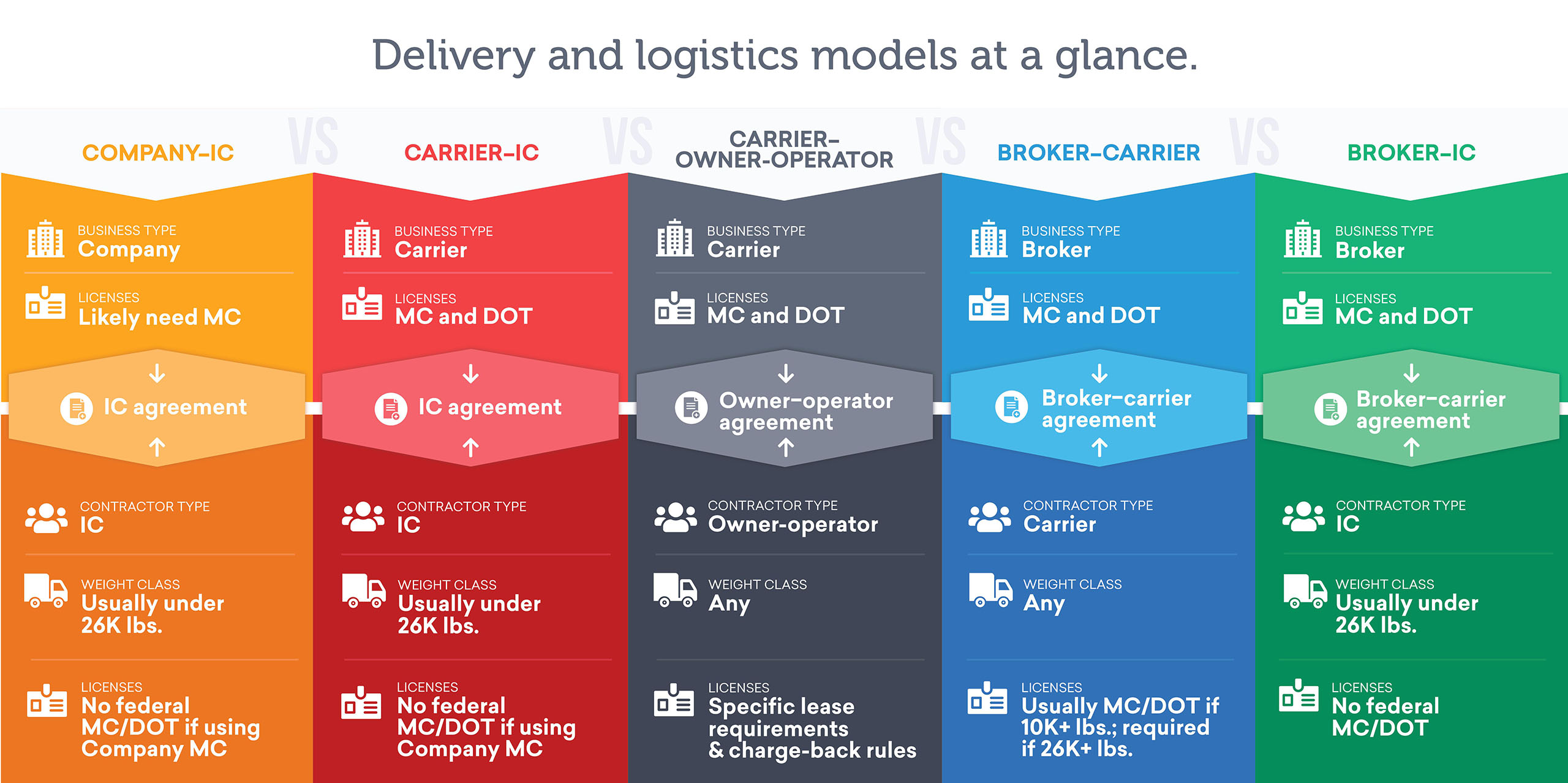

The transportation industry comprises a variety of different workforces and roles, from truckers to Uber drivers. For this discussion, we have narrowed these models down to those utilized within the delivery and logistics industries, where several types of contractual relationships exist between those who require transportation services and those doing the transporting. This approach allows us to break the models down into greater detail and examine the potential benefits and pitfalls of each.

Company–IC agreements

Take ride-share apps like Uber and Lyft. In this model, the company—an app provider—contracts directly with ICs—drivers—to provide a transportation service, many times to third-party “customers.” The ride-share company facilitates this relationship through their app, typically with ICs who own personal vehicles that weigh less than 10,000 pounds and carry fewer than eight passengers. In this scenario, neither party needs special licensing from the Department of Transportation (DOT), though there is a growing list of state and local regulations that may apply.

Carrier–IC/owner-operator agreements

Compare the previous model to federally licensed motor carriers who contract with ICs or owner-operators. ICs, once again, typically operate vehicles under 10,000 pounds without being federally licensed and rarely cross state lines. These Carrier–IC relationships are typically cast as service contracts without the “lease” of a vehicle—though, notably, even during “intrastate” trips, ICs are often carrying through or continuously moving goods (potentially rendering it an “interstate” load).

Owner-operators, on the other hand, can operate vehicles in any weight class and operate under the carrier’s federal MC and DOT licensing, and/or the state counterparts, depending on location. Either way, both parties are in the business of transportation, which can blur the lines between contracting company and contractor for the purposes of a misclassification test (like the ABC test and AB5 in California).

Broker–carrier agreements

Finally, we have broker models. A broker–IC agreement is typically for drivers of vehicles under 26,000 pounds in jurisdictions where no federal or state transportation permits/licenses are required. On the other hand, a broker–carrier agreement checks all the boxes: any weight class and both parties typically have their respective federal licensing. In this latter scenario, the broker—who merely arranges for transport—has a very different role from the motor carrier, who provides the service of transportation.

In the event a broker–carrier model is adopted, it is also prudent to ensure that all company insurance policies are reviewed by a knowledgeable transportation insurance agent for alignment with the new broker–carrier model. Failure to do so has potential risks that could void coverages. Openforce can help you connect with an experienced transportation insurance agent if you need assistance.

That said, this model provides a potential defense to the B prong of the ABC test because the broker and carrier are not in the same line of business—but we’ll discuss more on that later. First, take a look at the basic similarities and differences between these models.

These distinctions may seem confusing, but fully understanding each model and how to implement them correctly for your business can potentially provide a critical barrier against the ever-present threat of misclassification.

Motor carriers, misclassification and you

“Misclassification” refers to a variety of legal claims often collected under a single label. These can range from civil class action lawsuits to IRS audits to workers’ compensation claims. The theme that unites them is a company classifying a worker as an independent contractor when applicable law requires an employer–employee relationship.

A misclassification claim typically occurs for one of two reasons:

- Money: Satisfied contractors generally don’t file claims. You can often avoid misclassification by paying on time and accurately, specifying deductions ahead of time, and avoiding paying by the hour (i.e., pay by job, trip or route).

- Injury: Many ICs don’t have health insurance, meaning if they’re injured on the job, they may seek the most visible coverage—which is typically the contracting company’s workers’ compensation plan. You can often mitigate this result by requiring contracting ICs/carriers to be covered by an applicable occupational accident or workers’ comp policy.

The consequences for misclassification can be steep. Legal fees for defending against misclassification can rival the legal liability itself, which may include more than just damages awarded to an IC; it might include fines and penalties from the government or back premiums to an insurance company that didn’t realize they were providing workers’ compensation coverage to a number of “hidden” ICs. The combination of these is sometimes enough to put a contracting company out of business.

But that’s not even the scary part: Depending on the state you operate in and the type of misclassification claim being asserted, the law tends to be fuzzy on how to classify a worker as an independent contractor. In California, for example, legislators recently passed AB5, a law that codifies a notoriously difficult version of the ABC test used, at least in part, by more than 30 states. This test uses three criteria to establish whether a worker is an IC:

- The worker is free from the control and direction of the purported employer in relation to the performance of the work, both under the contract and in fact.

- The worker performs work that is outside the usual course of the purported employer’s business.

- The worker is customarily engaged in an independently established trade, occupation or business of the same nature as the work performed for the hirer.

The employer bears the burden of proof for each. Real problems arise from the B prong, which states the worker must perform work different from that of the contracting company. This rule makes it potentially difficult to differentiate between an IC and an employee in the transportation models outlined above, because both parties are in the business of transportation. In every model except the broker–carrier model, that is.

Advantages of the broker–carrier model

By far the most comprehensive approach to reducing your misclassification risk is the broker–carrier model, which offers a potential path out of the quagmire of the ABC test’s B prong. Because both parties perform different roles, it has the potential to satisfy the requirement and protect each party from misclassification and even third-party liability risks if certain best practices are followed.

Those best practices include:

- Using a standard broker contract for each carrier.

- Contracting only with carriers that have a business entity, such as an LLC.

- Selecting only qualified carriers who possess the required MC and DOT licensing.

- Possessing broker authority but not carrier authority.

- Contracting only with carriers who possess the required or appropriate insurances, such as occupational accident insurance.

How courts will interpret this model in relation to the ABC test remains a mystery, but it does appear to offer an additional layer of defense against misclassification when deployed as part of a comprehensive suite of best practices regarding independent contractors.

The only problem with this approach? Doing it the right way means higher costs and more time invested for ICs upfront. As a result, some drivers may go elsewhere. But there are ways to reduce this burden.

Simplify best practices with technology

Partnering with the right technology provider can alleviate much of the strain on contracting companies and ICs alike. For example, Openforce’s self-service platform empowers contracting companies to recruit, onboard, pay, insure and manage ICs. We also offer comprehensive occupational accident insurance; a Managed Business Setup program where a real person guides ICs through acquiring an LLC, EIN and MC/DOT numbers; and discounts on health insurance, auto maintenance and more.

But the real value of this technology is that it provides an additional layer between your company and ICs, potentially strengthening your business-to-business model as a result. That, in turn, bolsters your defenses and helps reduce your misclassification risk and third-party liability.

Openforce does not provide legal advice and is not a law firm. Although we go to great lengths to ensure our information is accurate and useful, Openforce does not represent or warrant that any information is fit for any specific purpose, nor should any portion of it be used without first consulting your own counsel.

About Openforce

Openforce is the leader in technology-driven services that reduce operating costs and mitigate risk for companies using independent contractors. Our cloud-based applications help companies and contractors alike achieve more sustainable, profitable growth by removing financial, operational, and compliance barriers to getting business done.